Shibli Zaman on Etymology [Revisited]

The Bluster Buster

|

"Pride goes before destruction,

a haughty spirit before a fall."

Proverbs 16:18

|

|

On July 18, 2003, I published the article ‘Shibli

Zaman and the Abuse of Etymology: Competing for the "Worst Etymological Fallacy" Award?’

discussing some of Shibli Zaman's many linguistic blunders, particularly various arguments

based on etymological fallacies. Zaman didn't take that critique very well and published

a reaction to it that

was, in my opinion, rather emotional and off-base. The following is my reply to his claims

and accusations.

| Suggestion to the reader: Make the interaction between Zaman's article

and my response below a test case for evaluating your own ability of critical thinking. Despite

my negative comment above, his article is actually a masterpiece of polemical rhetoric. Before

you proceed with reading my answer, read Zaman's article first — without being influenced by my comments —

so that you can appreciate the full force of his arguments. While you read ask yourself these

questions: Has Zaman made a good case? Is your main impression positive or negative? Why?

What elements or arguments in particular did you find convincing? Why? Is his case conclusive

or what is still lacking? What elements were distractive, insufficient, bad ... ? Why? Can you

find any arguments countering his claims? Write down your thoughts. Actually, the best training

effect would probably be achieved by reading in this sequence:

(1) Zaman's article with

the above questions, (2) my original article that

he responded to, (3) Zaman's

article again, asking yourself now the additional question: Has he actually rebutted my

article? Which arguments did he respond to, which arguments did he ignore? How does this effect

your evaluation of his response?

(4) While reading my answer given in this paper, you should be fair and consistent and ask

the same questions listed above also about my article. Compare your evaluation with mine.

Which of my observations and arguments did you find on your own? Have you made different

or additional observations? What is your conclusion after you have read my response? Has my

answer changed your view of Zaman's article in any way? Let

me know whether this was a worthwhile exercise for you. In fact, to add a little incentive,

for every further error of fact or error of logic in Zaman's article that is not yet covered

in this rebuttal, the first one to report it will get a free Answering Islam CD. The same offer holds for those who find substantial

errors of fact or logic (i.e., not mere typos) in my response. [Let me know about typos as well,

please, but I can't afford to send out prizes for them.]

Looking at the length of my response some may wonder about the reason why I am dropping

something like an atomic bomb to kill a fly (i.e., why I am "using a sledgehammer to

crack a nut" to employ a proper English idiom) since Zaman's actual argument could

easily be refuted in just a page or two. To answer within the word picture: Zaman had

also a whole host of other bugs in his case and I wanted to get rid of all the pests

once and for all. As you proceed you will come to understand the various related issues

I have taken up in my rebuttal. This article is mainly about recognizing and exposing

manipulative polemics, not just about answering an odd etymological argument. |

Zaman's manifold errors together with his excessive bluster and silly diversions

have necessitated a rather long response, which I have structured in the following way:

Part I — On bluster, insults and fallacies

Part II — Examining the evidence

Part III — Mopping up the leftovers

Part I — On bluster, insults and fallacies

Preliminaries

Zaman started his article with these words:

Bismillâh

"They can do no harm, but a trifling annoyance;

And if they engage you, they will turn and flee.

Then afterwards nothing will avail them."

[The Holy Qur'ân 3:111]

Jochen Katz Wins "Worst Etymological Fallacy Award"

Trying to make sense of one missionary's venemous ad hominem satire

I will do my best to prove the above quotation from the Qur'an to be a false

prophecy. There will be no turning and fleeing. Whether my arguments are indeed

strong and able to withstand the scrutiny of Muslim apologists, or whether they

are really no more than a trifling annoyance is a decision that I will

confidently leave to the judgment of the readers. Answering Islam has

engaged Muslim propagandists for many years, and I do not recount ever having

been put to flight, although many have announced that they will utterly defeat,

humilate or even destroy us.

Because I am so fully convinced that Zaman is a highly intelligent man,

I am baffled all the more to find that Zaman apparently failed in his attempt

to understand my article. Hardly as much as a trace of comprehending my main argument

is to be found in his response, although he clearly states in the subtitle that he was

trying to make sense of it. Is it my inability to formulate clearly, his inability

to understand plain English language, or was uncontrolled anger darkening Zaman's

mind for ten whole days from the date of publication of my article to the date

(7/28/2003) when he published his response?

The comprehension problems start already in the title that Zaman chose for his response.

The etymological fallacy

In my original article I explained the nature

of an "etymological fallacy", gave plenty of examples for illustration, and then discussed

several instances of this fallacy as committed by Zaman in his publications.

Admittedly, the title of my article was chosen provocatively, although

appropriately in my view since I was responding to an argument that

was not only fallacious but a deliberate ridicule of the Christian faith.

His argument was bad, and I called him to account for it, expecting that

a man like Shibli Zaman who has been moving in the arena of Muslim-Christian

debating for nearly ten years and who does not spare his opponents with sharp

attacks and scathing rhetoric, should be able to receive as well as he gives

and be a good sport about it. Oh well, ...

I have discussed and given evidence for several actual etymolgocal fallacies

found in Zaman's publications. Thus, Zaman qualified to enter a competition

about who committed the worst such fallacy. I had a factual basis to pose this

question in the title of my article: Competing for the "Worst Etymological

Fallacy" Award?

Answering this question was left to the readers since it is preposterous

for a debator to declare himself the winner. In any debate, the decision

who made the better argument rests with the audience.

Zaman seemingly didn't feel comfortable to leave that decision to the readership

of my article and his response, so he usurped the position of the judge and

unilaterally decided to give the undesirable award to me. I am sure not many

readers will appreciate being told what to think instead of being invited

to ponder the arguments and then decide themselves who made the more convincing

case.

However, in his rashness, and so desperately seeking to get rid of the trophy,

he overlooked that he cannot pass on the award to just anyone. Only those people

who have entered the competition can also win the award. I searched in vain

through all of Zaman's article but I could not find even one place where he

showed that I committed an etymological fallacy.

The etymological fallacy is a clearly defined logical error, it is not

just any error made regarding the etymology of a word. I had stated that

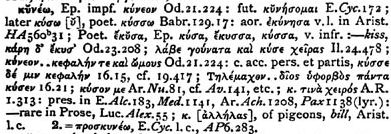

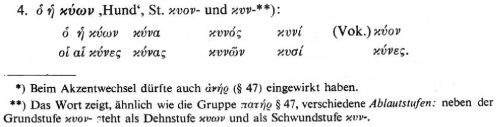

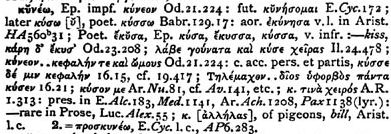

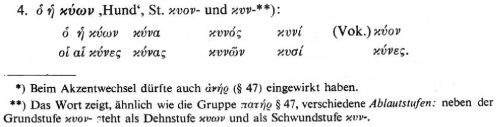

the Greek word kuneo is not related to kuon, and in his response,

Zaman argues that I am wrong, and that kuon is indeed the etymon of

kuneo. If Zaman's response turns out to be correct, then

I committed an error of fact, but not an etymological fallacy.

Even after such a detailed discussion of the issue, Zaman has apparently still

not understood what an etymological fallacy actually is. This conclusion

is not only based on his formulation of the title but is finally proven by the way

he presents his main argument (cf. Zaman's use and abuse

of Strong's). Zaman certainly needs to go back to the drawing board on this one.

His choice of the title for his "rebuttal" was nonsense on

a factual level, lacking creativity from a rhetorical viewpoint, and otherwise

merely petty and vindictive; and his choice of the subtitle again confirms that

last point.

Which part of Zaman's response was correct and which of his claims are not true

will be discussed below. If I made a mistake in this article or in other articles

(despite my best efforts to speak and write only what I am convinced to be true),

then I will own up to it, apologize and correct my errors. I do not consider

myself infallible. My highest priority is knowing and speaking the truth,

not defending my pride.

Although it should already have been unambiguously clear after I had

discussed the etymological fallacy in several places in my paper on

Zaman's abuse of etymology,

and additionally given further examples in my response to Zaman's article

Talking Ants in the Qur'an?,

he has seemingly still not understood the issue. Therefore, we have to revisit

the question: What is an etymological fallacy? In the following

I will supply several more quotations with definitions and examples, hoping that

one of these will eventually be understood. [Those who grasped the concept the first

time, are welcome to skip directly to the next point.]

ETYMOLOGICAL FALLACY

This is the name of a much-practiced folly that insists that what a word

“really means” is whatever it once meant long ago, perhaps even

in another language. A classic example is the argument that the adjective

dilapidated should be applied only to deteriorating structures made

of stone, because its ultimate source was the Latin lapis, meaning

“stone.” Actually, the Latin dilapidare meant “to throw

away, to scatter, as if scattering stones,” and the infinitive lapidare

meant “to throw stones.” And in any case dilapidated no longer

has anything to do with stones in American English; today it means “broken

down, fallen into decay or disrepair,” and it can be applied to any object,

garment, or structure, whatever it is made of. (Kenneth G. Wilson, The Columbia

Guide to Standard American English, Columbia University Press, 1993;

online source;

bold emphasis mine)

decimate (v.)

Today, decimate means “to destroy or kill or otherwise wipe out

a lot of any group or thing”: Disease and hunger have decimated

the population of the Horn of Africa. When we first acquired this

word from Latin, its meaning was “to execute one of every ten”;

it was the way the Romans punished mutiny in the ranks. Some commentators

have insisted on that as the only allowable meaning, but in fact it has

long been obsolete, and the extended sense meaning “to take away or

destroy a tenth part of anything” is at least archaic and perhaps

obsolescent. Even if you use decimate intending it to mean “to

destroy one tenth,” your audience will not understand it that way.

See ETYMOLOGICAL FALLACY.

(Op. cit.)

etymological fallacy. n. The mistaken notion that the true meaning

of a term lies in its primitive meaning (*etymology), that the earliest

historical occurrence of a term yields the correct definition. It is

a fallacy because the meanings of words evolve over time so that some

words are quite detached from their origins. Also called root fallacy.

See also illegitimate totality transfer.

etymology. n. The study of the derivation of words, both their forms

and meanings. Also used of the product of such a study. See also etymological

fallacy. (Source: M. S. DeMoss, Pocket dictionary for the study of

New Testament Greek, InterVarsity Press: Downers Grove, Ill., 2001, p. 53)

The etymological fallacy occurs whenever someone falsely assumes that

the meaning of a word can be discovered from its etymology or origins.

Example: The word "vise" comes from the Latin "that which winds", so it means

anything that winds. Since a hurricane winds around its own eye, it is a vise.

(Fallacies

[Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]; bold emphasis mine)

Some philosophers have the vice (bad habit) to be complicated and use obscure

examples. I certainly did not know what a "vise" was when I found the above quotation.

A vise

is a "clamping device, usually consisting of two jaws closed or opened by a screw or lever,

used in carpentry or metalworking to hold a piece in position (The American Heritage® Dictionary

of the English Language).

The final and longer quotation about the false use of etymology is taken from

a language discussion forum:

It seems to me that in the past, the etymology of a word was erroneously

believed to have some bearing on its 'correct' usage. Perhaps this belief has

been stronger in the English-speaking world than elsewhere. Perhaps

we Anglo-Saxons are haunted by a word's history more than we should be.

When Samuel Johnson was compiling his Dictionary of the English Language

(1775), I believe he was often swayed by the history of a word when making

one of his silly, arbitrary decisions on its spelling (yes, you can all

blame him:)). So he decided to stick a b in 'doubt' because the Latin word

had a b in it, even though nobody else had ever pronounced or written a b

in the English word until he came along.

Even nowadays, reference to a word's earlier meaning can often influence the

way an argument proceeds. In a recent TV debate on the way history should

be taught in schools - whether the focus should be on 'facts' or 'methods'

- a supporter of the latter position referred to the 'real' meaning of history

as 'investigation' or 'learning by enquiry', as this was what was meant by

Greek historia, from which the modern term derives. Several people were

swayed by the point, and referred to it throughout the debate.

This view that an earlier meaning of a lexeme, or its original meaning, is

its 'true' or 'correct' one is called the etymological fallacy. The fallacy

is evident when it is realised that most common lexemes have experienced

several changes in meaning during their history. 'Nice', for example,

earlier meant 'fastidious', and before that 'foolish' or 'simple', and if we

trace it back to the equivalent Latin form, 'nescius', the meaning is 'ignorant'.

(Source: Posting on CzechList;

bold emphasis mine)

[In the archives of "Merriam-Webster OnLine" one can find an etymological argument

about the meaning of a couple, and so I am providing a couple of further interesting

and/or educational links:

Sites about Etymology,

Words Mean Things,

Reasons for

Language Change, The influence

of the Greek language in English,

An etymologist

on Chauvinism, Semantic

Anachronism. The collection of links in this paragraph is somewhat random

(one can find hundreds of pages on the topic), but nearly all of these are

providing comments about, or examples of etymological fallacies.]

Dr. Campbell's book The Qur'an

and the Bible in the Light of History and Science has a detailed discussion

on The Etymological Fallacy

(since Zaman's articles are not the only Islamic publications containing these errors).

My recommendation would be to read not only that section but the whole chapter

titled Basic Assumptions About Words

to gain a deeper understanding.

Sadly, the displayed lack of understanding in regard to certain logical fallacies did not

end here. The second comprehension problem is found in the very next line, i.e. Zaman's

chosen subtitle, "Trying to make sense

of one missionary's venemous ad hominem satire." Thus, the next concept

we have to discuss is ...

The ad hominem fallacy

It is a favorite move by Zaman to accuse those who dare to critique and oppose his

theories of ad hominem attacks on his person.

However, just as Zaman has seemingly not understood what an etymological fallacy

actually is, he also appears to be ignorant of what constitutes an ad hominem,

and what doesn't. Others have also commented on the abuse of

calling

everything an ad hominem.

Let me present two claims to illustrate the issue:

- Zaman's argument is wrong, because he is not a recognized scholar of linguistics.

- Because Zaman's linguistic arguments are frequently wrong,

therefore he is not a scholar of linguistics.

Zaman may feel much more attacked by the second statement than by the first one,

but only the first one is an ad hominem. Regarding its structure, the second

statement is a valid inductive argument.

The truth of an argument or claim is independent of the age, religion,

academic achievement, character or manners of the person who makes the argument.

Thus, pointing to some (negative) characteristic of the person who makes an argument

in order to undermine the argument is committing an ad hominem fallacy (which

is the structure of claim A.). There are many sites that discuss logical fallacies.

Some of the best, most thorough and most comprehensive are listed in the general

references section on our Logical

Fallacies page. All of these have good explanations of what constitutes

an ad hominem argument. There is no need to repeat that here as well.

For this particular fallacy, my favorite explanation among all those is

this detailed discussion. It may, however, be worth pointing out

that ad hominem does not mean "against the man" as it is all too regularly rendered,

even on a number of websites that discuss logical fallacies. Zaman seems to think similarly

since twice in his response he called my article an "ad hominem

attack against me". Most of the Latin names of these fallacies have

the preposition "ad" in them. Some examples: argumentum ad misericordiam

is the appeal to pity, argumentum ad ignorantiam is the appeal to

ignorance, i.e. an argument based on ignorance, not an argument against ignorance,

ad baculum denotes "scare tactics", i.e. it is the appeal to emotion (fear).

[The Latin word for "against" would be "contra" (cf. pro and contra) or "adversus"

(cf. adversary).] Most clearly perhaps: argumentum ad verecundiam, the appeal

to authority, is not an argument against authority, but denotes the fallacy of

appealing to an alleged authority (that may not even be an authority) instead of

arguing the case with the relevant facts. Similarly, ad hominem

denotes arguing in regard to the man, i.e. pointing to some element in

the character or circumstances of the person. It is not an argument against

the person who makes it, but against the claims made by that person on the basis

of some unrelated personal characteristics. For the next paragraph, I am going

to assume that he will make himself thoroughly familiar with the concept before

answering this ...

Challenge to Mr. Zaman: Show me even one instance of an ad hominem argument

in my first article discussing your fallacious

etymological arguments since you labeled it an ad hominem attack on

your person several times in your response. In fact, show me where I use

an ad hominem argument against your claims and theories anywhere

in the several articles that I have written in

response to your publications.

On the contrary, it is Zaman who used a large number of ad hominem elements

in his presently discussed response in order to weaken the impact of the arguments

presented in my original article.

This begins already in the subtitle, "Trying to

make sense of one missionary's venemous ad hominem satire",

containing several such elements:

missionary: The meaning of words is

determined by their context. For Christians the word "missionary" is a positive

term. In the largely secular and pluralistic western society the word carries

today mainly negative connotations. For Muslims it is an extremely negative word,

one of the worst insults, completely discrediting the person such labelled. In

the general Muslim understanding missionaries are people who actively fight

against the truth of God (Islam), and who seek to poison the minds of Muslims

with their falsehood (the Gospel). Whether my arguments about general linguistic

principles and the facts regarding the etymology of a particular word are correct,

has nothing whatsoever to do with the question whether I am a missionary

or not. Zaman's claims were not written for me, but for the public. My original

article discussing Zaman's etymological errors was not primarily written for Zaman

either, but for the same public audience, and that is mostly a Muslim readership.

The term "missionary" was only introduced into the discussion in order to create

a highly emotionally charged, negative attitude towards me and my arguments

in the Muslim audience addressed by Zaman. As such, it is the classical

ad hominem argument.

True, Zaman does not state explicitly that my arguments are wrong,

or that I should not be taken serious BECAUSE I am a missionary, but if

that effect was not his intention, why did he introduce the term at all?

venemous: Whether a certain argument

is presented in a venemous way, or driven by a motivation for hurting somebody,

may indeed be important to determine in some circumstances. But again, whether

an argument is venemous or not, that has nothing to do with the issue whether

it is TRUE or not. [There are venemous arguments that are true, and there are

arguments made calmly or even out of love which are nevertheless wrong. Manner

is also important, but manner and motivation do not determine truth.] Venemous

is without doubt a negative term and we do not like people who are venemous.

By using this word, Zaman is again seeking to turn the opinion of the reader against

me in an emotional way BEFORE he even begins to discuss the content of my arguments.

This the second ad hominem element of Zaman's subtitle. Note: Zaman does

not actually give any evidence that my article was venemous. He only accused

me of it. This is very poor style.

ad hominem: Everyone these days knows

that using an "ad hominem" is a bad thing, even though many do not know exactly

what it is. But it is something like "being against somebody", and this accusation

communicates that the other person is not rational (after all, it is a fallacy).

Zaman obviously felt attacked by me, so he just accuses me of arguing

"ad hominem". Like the word "venemous" this accusation has only the purpose

to make me look bad. Zaman repeats this charge twice in the article, but he

does not establish an actual incident of an ad hominem on my part.

These three expressions are the main elements, but there are a couple of minor

ones as well: "Trying to make sense of ..."

communicates that my article was incoherent (again without proof). Finally,

the word "satire" seeks to disqualify

the article from being a serious discussion, but being instead something that was

merely seeking to make fun of him. I readily admit that there were some satirical

elements in it. But taken in its entirety, the article was a serious discussion

of linguistic principles and etymological errors, and not a satire.

It is sad enough that I had to explain the concepts of an etymological

and an ad hominem fallacy. I am not going to define and discuss also

the literary genre of "satire" for Zaman. If he wants to know more about satire,

he should go back to school and ask his highschool teacher of English Literature

about it. [Yes, that last sentence was sarcastic.]

Zaman has peppered his whole article with such ad hominem attacks, insults

and unproven accusations against me and/or the style of my article. Though most of

them are not formally ad hominem arguments, they serve the same purpose in

the context of the article, and will therefore be treated the same way. Apart from

a few particularly bad examples, I will not discuss these any further since they do not

contribute anything to determining the truth in the matter of our disagreement. From

now on, I will mark them in bright red color in the quoted

parts of Zaman's article to make the reader aware how ubiquitous they are.

Some thoughts on scholarship

I need to come back to the second form of the claims mentioned above:

- Because Zaman's linguistic arguments are frequently wrong,

therefore he is not a scholar of linguistics.

This one really seems to be Zaman's problem with my articles, although it is not

ad hominem. This is indeed the approach I am taking and it is a valid inductive

argument drawing conclusions from observed data. When discussing Zaman's individual

arguments — whether linguistic, historical, or theological arguments —

I have never appealed to Zaman's lack of academic qualifications in order to establish

that his argument is wrong. When I disagree with Zaman's claims, then I carefully discuss

the facts, the sources, and the implications of the observed data. I explain where

I disagree with his argument, why I think he is wrong, and what

I propose as an alternative and more appropriate understanding. That is, after all,

the whole purpose of academic discourse. Bring the competing theories to the table

and seek to make the best possible case for the understanding that you are personally

convinced of, ... and this process includes pointing out the errors and shortcomings

of the other proposed theories.

Zaman, however, does not only make linguistic or theological arguments. If there

would only be a certain academic argument about language, history or theology,

then we could discuss the truth of it on that factual level and be done with it.

But that is not the way Zaman operates. In his articles published on the web and

in his contributions to discussion boards he makes many explicit and implicit

claims about his superior knowledge and scholarship (see also the discussion about

the name of his website). These claims are

an integral part of his arguments, and therefore these personal claims become

a legitimate topic of discussion. They are subject to evaluation just as all the other

claims. My critique of his personal claims may feel to him like a personal attack

(thus his false charge of ad hominem attacks), but since Zaman constantly

questions others regarding

their qualifications and denigrates his opponents for their supposed lack of knowledge,

it is only fair that his own alleged qualifications become the subject of evaluation

and critique.

The above stated claim B is thus a two-fold argument since I first need

to establish that his arguments are indeed wrong, i.e. the structure is:

- Showing which of Zaman's arguments are wrong and why they are wrong.

- Because his arguments are so frequently wrong, therefore Zaman cannot

legitimately be considered a scholar of linguistics.

This is an inductive argument that is both appropriate and valid. There is nothing

ad hominem about it.

Everyone makes mistakes, even scholars, both accidental mistakes (i.e. he really

knew better) and genuine ones (i.e. he was wrong about this detail despite his

conviction to the contrary, and his otherwise unquestionably vast knowledge in

the field). Making an occasional mistake does not mean that a man is therefore

not a scholar.

Getting a first degree (BA or BS) in a certain field usually means that the person

has learned the basics and foundations and should have a thorough understanding of

the main issues in the field. With that, a person may call himself a professional, but

earning such a first degree in a field is not the same as achieving the status

of a scholar.

The scholarship of a person in a particular field of studies is established on

the basis of his comprehensive knowledge together with genuine and original

contributions to this field which are recognized by his peers. Usually these

contributions are made in the form of peer-reviewed articles in scholarly journals

and/or the publication of books in academic publishing houses.

If, however, a person claims extensive knowledge or even scholarship in a certain

field but constantly makes substantial mistakes in the area of his alleged expertise,

particulary very elementary mistakes that not even an undergraduate in the field

would make, then this is solid evidence that his claim to scholarship is

vacuous, and the person is either deluded (sincerely believing to be

something that he objectively is not), or he is an imposter (claiming to be

something while knowing very well that he isn't).

Then there are the amateurs, those who love a certain subject, who have done some,

or even much reading in the field, and they spend much of their leisure time on this

hobby. They are people who are dabbling in the subject more or less extensively, but

who have never received a solid education in the field. Even though they know quite

a bit — and due to their passion for it they may even know more about certain

aspects than many professionals — they often lack a thorough knowledge of and

training in the foundational methods in this field and are therefore prone to make

elementary mistakes. Particularly amateurs may easily become over-confident and delude

themselves regarding their status as "experts", i.e. thinking that they know more

about the field than they actually do.

What about linguistic scholarship? For the English language it is clear to

most native speakers that being able to speak the language fluently does not yet

make one an English language scholar. This is no different in any other language,

whether be they "current languages", i.e. contemporary French, German, Arabic, or

Hebrew, or "ancient languages" like Classical Greek, Biblical Hebrew, Quranic Arabic,

Latin, Sanskrit, etc. Learning the alphabet and thus being able to decipher the entries

of a dictionary does not make one a scholar. Learning a language up to reading

proficiency does not make one a scholar, and even learning a language to the degree

that one can speak it fluently and nearly error-free may bring a person up

to the level of a native speaker, but does still not automatically make one a scholar

of that language.

One more important aspect of true scholarship needs to be highlighted. Scholars know

that many of their theories are tentative, and they welcome critique because

it helps them to sharpen their thinking, deepen their understanding, and will lead

the whole community of scholars to come closer to the truth. Seeking the critical

review of other scholars is the foundation of progress in scholarship.

Zaman, on the contrary, is propagating certain convictions as the established

and absolute truth. If anyone dares to critique his claims, he gets horribly

offended, and will then defend his errors tooth and nail. This behavior alone

is evidence that he does not move in the community of scholars

and has not understood how (western) scholarship works. [Islamic

‘scholarship’ may operate under a completely different paradigm.]

Coming back to the issue of ad hominem, it is somewhat ironical that an

ad hominem argument is exactly the opposite of what Zaman thinks it is.

Ad hominem would be a critique and dismissal of Zaman's arguments

based on his lack of academic qualification / scholarship (without

evaluating the argument itself). On the contrary, after giving proof that

his arguments are wrong, I am then criticizing his claims to scholarship

based on his bad arguments. Zaman is then offended and therefore

accuses me that this is an ad hominem attack on his person. It is not.

Usually it is silly to debate a title or headline of an article. Titles have to be

short and therefore can only give a very limited clue of what the article is about.

The serious interaction needs to be with the body of an article and the arguments

presented there. In this case, however, the choice of his title

already revealed so much about Zaman's lack of understanding that this discussion was

justified. The founder / president / director of the "Near

Eastern and Semitic Studies Institute of America" is throwing around a lot

of big words that he does not even understand.

This said, let us move on to the body of the article.

Going from bad to worse (Examining a cacophony of bluster, insults and the like)

Zaman warms up with:

I. Introduction

Jochen Katz is definitely a master of illusions.

At "Answering-(Attacking)-Islam" they employ a number diversionary

tactics to supplement their lack of knowledge or evidence. One such tactic

is that if there is no quality to the argument, they employ a whole lot

of quantity.

As indicated above, both insults and ad hominem arguments will from

now on be in red, though it will not always be explicitly discussed why they are

ad hominem. The rest of the quotations from Zaman's article will be in green.

To some people it is given to formulate very concisely. Others are more wordy.

I have never claimed that my writings have a high literary quality. I am concerned

about truth. I agree, my articles tend to be long, but the reason is my urge

to be thorough, comprehensive, and to cover all my bases.

The quantity of words has, however, nothing to do with their truth. There exist

long books which are true, and there are very concise but wrong statements.

[Thus this is another (circumstantial) ad hominem.] Zaman uses again a long

list of big words, but it has no other purpose than to poison the well.

Ironically, paragraphs like these — and there are plenty of them —

only make Zaman's articles longer without contributing anything to

the substance of the discussion.

Had Zaman first carefully discussed my article, had he been able to show that

it actually lacks quality, and then concluded that it seems I am using quantity

to substitute for quality, that would have been the proper approach. However,

he ignored most of the article — including various very relevant sections that

are actually refuting his current arguments and which will therefore be requoted

in this paper. Instead he complained about the length of my paper several

times during this article as if length itself speaks against quality.

Taking this "argument from quantity" to its ridiculous conclusion, then Surah 2

of the Qur'an would be less trustworthy or of lesser quality in some respect

than Surah 96 because it is so much longer, and finally Zaman's own website

will automatically become less accurate the more material he adds.

For this paper I could just have quoted the scholarly standard reference on the etymology

of Greek words and said: This settles the case, and all arguments constructed by Zaman

in support of his claim are merely linguistic nonsense since there is (today) not

one scholar who holds to Zaman's etymological hypothesis. However, Zaman could

then have accused me of the fallacy of appeal to authority and would

definitely have charged me to be unable to deal with his arguments. Therefore,

I am going to discuss each of Zaman's arguments in detail, and will explain

why I consider them wrong. An explanation of what is wrong and why it is

wrong is nearly always much longer than the false claim itself. Moreover, since

most readers do not know much about Classical Greek, I need to give sufficient

background to enable them to follow the arguments about Greek grammar that are

involved in this issue. (Don't worry, this article will not be boring.) I hope

this sufficiently explains the length of the last as well as the current article.

Finally, let's have a quick look at the epithet "master of illusions". Apart from

the fact that most of Zaman's current article will turn out to be one big illusion,

this is really "the pot calling the kettle black" (although Zaman fails to show

that the kettle is actually black). Just have a look at my observations and questions

in the shorter article Who or What is NESSIA

really? to see what I mean.

Zaman continues:

Apparently, these guys have no shortage of spare time. Often

they bawl out pages upon pages of rhetoric which could be summarily stated in just

a few sentences. Any visitor of their site can see this lucidly. The point is to overwhelm

their victim with an insuperable barrage of messy rhetoric

in hopes that he simply won't bother responding. After all, we did

not receive a grant $500,000 dollars from the Bush administration.

We have jobs to tend to. This leaves us little time to address an overflowing

multipaged septic tank from "Answering-(Attacking)-Islam".

I will ignore all the other insults that are merely silly, but this particular

circumstantial ad hominem is one of Zaman's favorites. In another one of his

articles, REBUTTAL:

Fire Under the Sea - Part 2, Zaman wrote:

Bushism par excellence – "Lexicographical Inexactitude"

First, with all due respect to Mr. Austin, I couldn't help but laugh at

the very start of this "rebuttal" and I knew I was in for a whole torrent

of lexical and logical bungles a la good ole G. Dubbya who is funding

THEM with an initial grant of half a million dollars of American tax-payers'

money. Birds of a feather flock together.

(underline and capital

emphasis mine)

Even though in this case, Mr. Austin did indeed use the wrong word, Zaman's claim

of us having received money has nothing to do with the truth or error of Mr. Austin's

arguments in his article, or the truth of my arguments in the etymology article.

Maybe I have to spell it out for Zaman by way of an illustration he can understand?

Imagine a rich Muslim discussing with a poor Christian about the true faith, and

another discussion between a rich Christian and a poor Muslim. What is the relation

of truth to money? None.

Furthermore, since Zaman does not give any evidence of us having received

such money, it is slander and false testimony. In fact, Answering Islam has

never received even one cent out of US government funds, let alone from Mr. Bush's

personal funds. On the other hand, it is well known that the Saudi government alone

spends billions of dollars every year on spreading Islam worldwide, and they are

not the only government of the Islamic world that invests in this cause. This fact

is not an argument against the alleged truth of Islam, but it is exposing the duplicity

in such arguments. [For plenty of logical bungles you only need to go back

to the beginning, for lexical bungles, see below

and also on this page.]

Actually, this same paragraph exhibits yet another fallacy:

Apparently, these guys have no shortage of spare time. Often they bawl out pages

upon pages of rhetoric which could be summarily stated in just a few sentences.

... The point is to overwhelm their victim ... in hopes that he simply won't bother

responding. After all, we did not receive a grant $500,000 dollars from the Bush

administration. We have jobs to tend to. This leaves us little time to address an

overflowing multipaged septic tank from "Answering-(Attacking)-Islam".

(bold emphasis mine)

The first fallacy was that this alleged wealth is somehow subtracting from the truth

of our argument (perhaps even tainting our moral standing and character). In reverse,

this is also an example of argumentum ad misericordiam (appeal to pity).

Basically it says: please accept my arguments because of my unfortunate situation

compared to my opponent who has a lot of money.

Zaman continues with these words:

In this manner, Jochen Katz launched a scathing

15-page ad hominem attack against me, personally, in which he tried to

discredit my ability in Semitic linguistics. Laughably, he chose to do this by arguing

over a side comment I had made in "Stung From the Same Hole Twice" which contained a

tongue-in-cheek reference to a Greek word in the Gospels (Greek is an

Indo-European language and not Semitic).

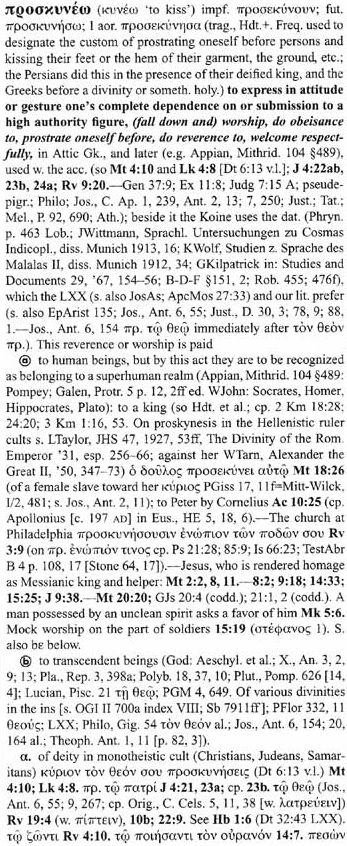

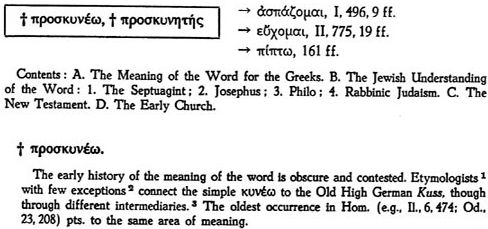

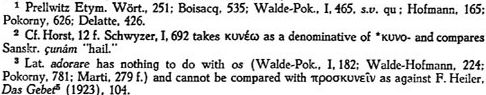

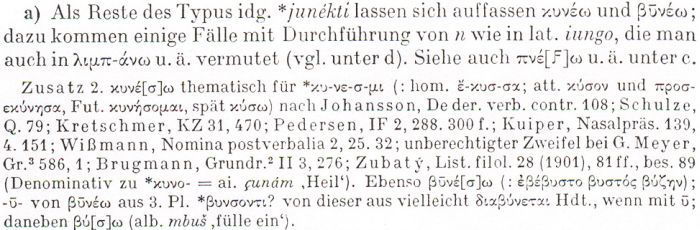

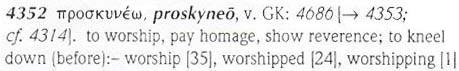

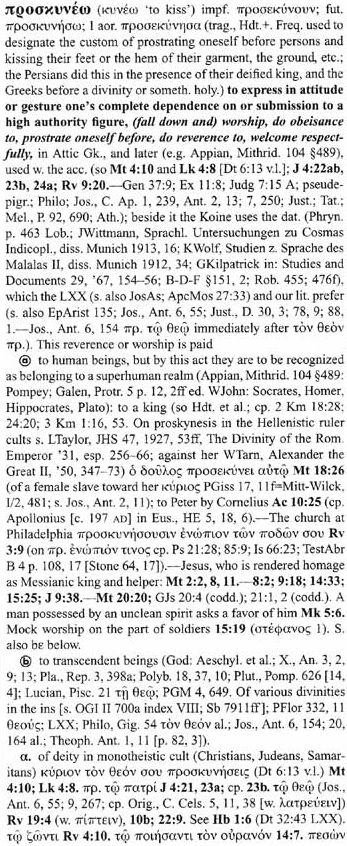

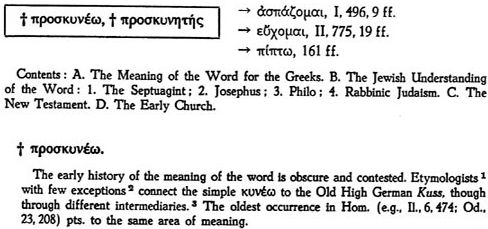

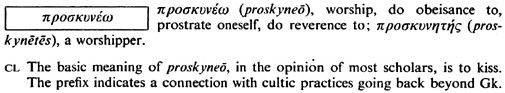

The word is pros-kunew (προσκυνεω)

which I stated has its etymons in pros (προς) being of

association and kuwn (κυων) being a dog. Thus, this

particular Greek word for "worship" has an etymological ancestry in "groveling

like a dog".

First, I know the difference between Indo-European and Semitic

languages quite well. I have certificates from accredited institutions in both

Classical Greek and Biblical Hebrew. The difference between Zaman and myself is

that I never felt the need to brag about my ‘linguistic scholarship’.

I am not at all trying to discredit Zaman's ability. That is definitely

the wrong choice of words. In order to discredit an ability one has to assume

there is an ability to discredit in the first place. On the contrary, I am

exposing Zaman's inability.

Second, I never questioned Zaman's knowledge of Semitic language on the basis of

his ignorance of the Greek language. This is another unproven claim by Zaman. In my

first article about Zaman's Abuse of Etymology

I discussed etymological fallacies committed by Zaman in two languages, Greek

and Arabic. The fact that the meaning of a word is not determined by its etymology

is a general principle that holds for all human languages. I pointed

out that Zaman is violating this basic linguistic principle over and over again

in his arguments made about different languages. I am well aware that Zaman's

knowledge of Semitic languages is vastly greater than his nearly non-existent

knowledge of Greek. However, this greater knowledge does not hinder him from committing

the same basic linguistic errors even in Semitic languages.

So far we have collected the expressions etymological fallacy, ad hominem

and satire as unclear terms in Zaman's English vocabulary. Those are admittedly

more complex concepts. The above paragraph seems to introduce another problematic

expression. Could it really be that Zaman does not even know the meaning of

tongue-in-cheek? Let me present some dictionary definitions:

tongue-in-cheek

Ironically: "The critic’s remarks of praise were uttered strictly tongue-in-cheek."

(The New

Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition. 2002.)

Speaking insincerely; jokingly. ... not being serious.

"He cried 'superb! magnifique!' (with his tongue in his cheek)."

(Source)

if you say something tongue in cheek, what you have said is a joke,

although it might seem to be serious

'And we all know what a passionate love life I have!,' he said, tongue in cheek.

(Cambridge

International Dictionary of Idioms)

Meant or expressed ironically or facetiously.

(The American Heritage®

Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000)

characterized by insincerity, irony, or whimsical exaggeration

(Merriam-Webster OnLine)

joking: spoken with gentle irony and meant as a joke

(Encarta® World English Dictionary)

... indicates that someone just told a joke or isn't being serious! ...

(KidsHealth)

Did Zaman really intend to say in the above that he was not being serious

in his original article and his argument was only a joke? If he meant

indeed tongue-in-cheek, then this is a cheap cop-out because

his argument was definitely not meant jokingly. Anyone reading his

original article

can see that. If it had just been a joke, and Zaman knew that this interpretation

was not really true, then he should now have admitted to it, apologized that

the joke was in bad taste and moved on. Is that what we see? Not at all. It was

not a "side comment" but an integral part of his case, and there is absolutely

no indication in the article that it was written jokingly. Zaman was dead-serious

about it. That is why he wrote this current response the way he did, making such

an elaborate effort for the defense of his original argument, and

he is still claiming that he was right.

It is really very simple: If it was tongue-in-cheek, then it was not true,

but since Zaman makes great efforts in this article to prove it was true, he is

himself providing the evidence that it was not tongue-in-cheek.

Zaman is trying every trick in the book to avoid taking the responsibility

for his errors. Defend every error to the utmost; and should that finally fail,

claim it was meant as a joke, so that it is still not an error on his side,

but a lack of discernment on my side for not realizing that it was a joke.

Stop playing games, Mr. Zaman! You will only hurt your own credibility because

I will not let you get away with this kind of manipulative rhetoric.

We continue with Zaman's text:

My article which he cited had absolutely nothing to do with the Bible or etymology.

It had to do with the Muslims of America coalescing into a voters' bloc against the

Bush administration in the upcoming presidential elections. However, as

Jochen in his understandably limited abilities had trouble finding something

to attack here on the NESSIA website, he blindly shot in the dark. As we shall see

he repeatedly shot himself in the foot while doing so.

II. Slamming the door shut before it even opens

Looking at Zaman's discussion of the Bible story and its application, i.e. from the subtitle

"The crumbs that fall ..." up to the conclusion "sadly it has worked well", one finds

that this section takes up 462 of 2751 words or 18% of the body of his article (i.e. without

header and footnotes), an article that supposedly "had absolutely

nothing to do with the Bible." Even when looking at this merely quantitatively,

eighteen percent of the text of his article was precisely to do with the Bible —

it formed a fairly large tangent from his original article.

Furthermore, Zaman indirectly confirms the comment that I had made in my original article:

"Taking a stab at the Bible in this context appears to point to an insatiable desire to

attack the Christian faith even when talking about issues that are completely unrelated

to Christianity." Interestingly, Zaman avoided to explain in his response why

he introduced this issue in the first place.

Does Zaman really think I have trouble finding something to disagree

with on the NESSIA website? Certainly not. It is only another one of his

rhetorical tricks, since on the same day that I published the article on

Zaman's Abuse of Etymology, I also

published two other articles: Reflections on Muhammad's

saying "The believer is not stung from the same hole twice" (so far completely

ignored by Zaman), and my rebuttal to his Talking

Ants in the Qur'an? In the meantime, several more articles have been added

which can all be found in the Zaman Rebuttal Section.

Instead of trying to play down his claim as a "side comment" or even as being

"tongue-in-cheek" on the one hand, and then nevertheless defending it as true

on the other, Zaman would have done much better to admit his mistake, apologize

and move on. Given the course he has chosen for himself, we will soon see who

is aimlessly shooting in the dark and whose foot will end up being full of holes.

His second subsection heading, "Slamming the door shut BEFORE it even opens"

is another ‘masterpiece’ from our virtual language scholar. [Note for

Zaman: this last sentence was tongue-in-cheek.] This incoherent word picture

is actually endearing in its emotionality. Just imagine it for a few seconds,

how Zaman is trying hard to SLAM a closed door without first opening it!

This first part of my response, i.e. everything up to this place, has been designed

with the express purpose of exposing Zaman's polemical approach, his bad methodology, and

his empty rhetoric which is wholly unbefitting for anyone who wants to be considered

a scholar. As far as the public evidence goes, Zaman is hardly interested

in genuine scholary interaction but is mainly an Islamic apologist and

polemicist.

Everything stated so far is not part of my argument against Zaman's

etymological claims. My evaluation of his alleged evidence connecting the Greek

words for "worship" and for "dog" is completely independent of it, and will

now be presented in the second part of my rebuttal.

Part II — Examining the evidence

What's at stake?

Let me first remind everyone what actually is the topic of discussion. Despite Zaman's

complaint that the length of my article completely overwhelmed him, my main argument

was stated so early in the paper that there is no valid excuse for Zaman to have

missed it. I wrote:

The first lesson any linguist or serious language student has to learn

is that the meaning of a word is determined by usage not by etymology

(let alone false etymology as in this case).

I substantiated the validity of this principle with many examples as well as

quotations from recognized linguists and showed how Zaman repeatedly

violated this foundational principle. What was his response? He completely

ignored the main argument of my article and focused solely on the side remark

that is found in parentheses in the above quotation.

He aggressively sought to defend that his etymology was actually correct,

although even a correct etymology would still leave him with having violated

this basic principle and having committed the etymological fallacy. After

deriving what I considered to be the correct etymology of the word proskuneo,

I then explicitly stated:

Still, proskuneo doesn't mean ‘kiss towards’ but prostrate,

make obeisance, worship. In this case and in most cases, even if you get

the etymology right, this still doesn't get the meaning right. To investigate

the meaning of a word, look at how it is used. Its history is amusing and might

educate us in interesting ways, but is not a reliable source of evidence on

its present meaning.

The sole question for the exegete is this: when a first century author deployed the lexeme

proskuneo what referent did he intend?

The topic of my article was the meaning of proskuneo not the

etymology of the word, even though I also discussed its etymology.

Zaman attacked an absolutely minor point in the overall argument and made

a huge brouhaha about it. Even if everything Zaman wrote in his response

were to be correct, he still lost the case because the meaning of a word

is not contingent upon what it may have meant a thousand years ago since words change

their meanings over time. The issue is what it means in the context it is used.

Apparently, Zaman has still not understood this. I provided more than a hundred

references to Greek texts in which proskuneo without doubt means "worship",

while Zaman has — despite digging around in various dictionaries —

not been able to present even one reference to a Greek text that would support

the hypothesis that "groveling like a dog" is even a possible meaning,

let alone being the real or main meaning of the word, which was Zaman's

original claim.

Let me compare what is going on here with a game of chess. During one particular

game, Player A made a very bad move, and this silly oversight cost him one of

his pawns without anything in return. Player Z took that pawn from the chess board

with a triumphant look on his face. In the end, however, it was player A who won

the game.

For months after this game, player Z goes around deriding player A for being

a really bad chess player because he made such a stupid move ...

How impressive would that be? An admirable display of sportsmanship by player Z

by any standard! What does really count? The game or the pawn?

Be a man, Zaman, and face up to the fact that you lost this one, and

that it is insubstantial whether I lost a pawn on the way or not.

A public admission by Zaman of having lost an argument is, however, a very

rare collectors item indeed. For others Zaman always has some good

advice:

To those who compromised their objectivity in a bid to save their personal religious

beliefs we say: If archaeology scores a point against you today, you might score

one against it tomorrow, but objectivity must never go up for sale.

(Shibli Zaman, BREAKING NEWS:

James Brother of Jesus Ossuary a Fake, 18 June 2003)

Does that good advice only hold for issues in archaeology or does it

also hold for linguistic arguments? Is that the proper behavior only for others

or also for Zaman? At least we can say this: Zaman is consistent in being

inconsistent.

When a sportsman of honor loses a game, be it a game of chess or a tennis match,

he will publicly approach the winner, shake hands and congratulate him. Zaman

does not deny that my main argument is true. He completely ignores it. Instead

he rails on and on about how bad I am because I lost that pawn. I am not impressed.

Anyway, let's move on. In order to determine whether I even lost that pawn,

let me turn to the evidence that Zaman presented to support his original claim.

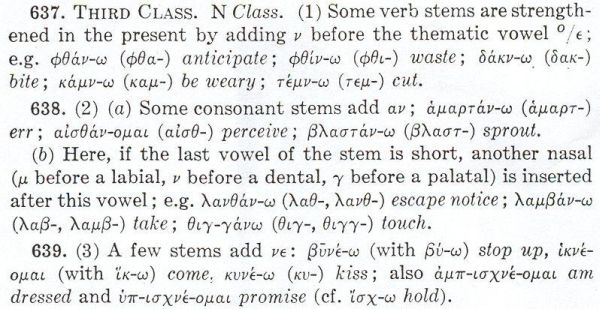

Strong's Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible

Zaman's use of Strong's

We now reach the section where Zaman played his ‘trump card’:

II. Slamming the door shut before it even opens

Jochen states about my etymological analysis:

"Zaman should have researched his claims better instead of just assuming that

the results of his armchair etymology are an established fact."

In spite of Jochen's harangue being 15-pages long, this will relatively be one

of the shortest rebuttals in history. For starters, to the above comment allow

me to produce the following:

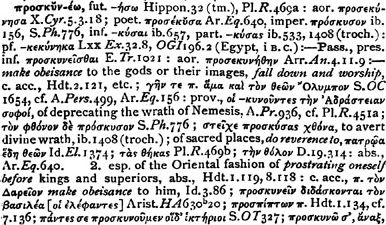

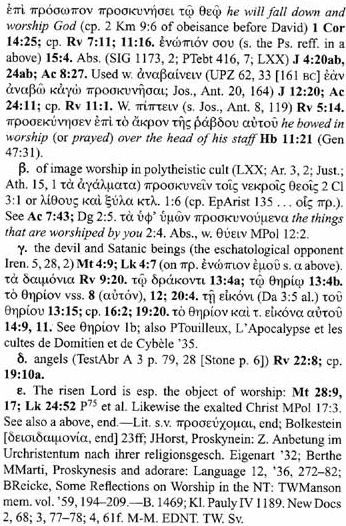

[Strong's Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible,

James Strong, LL.D., S.T.D, 4352, p.61 of Greek-English Dictionary; actual scan]

That’s it. The end.

So even if Jochen wa

[sic] absolutely right that

the word pros-kunew (προσκυνεω)

has no etymological relationship to kuwn (κυων) for "dog"

(which he is most definitely not), then this is not my "etymological

fallacy" but it is James Strong's. Thus, the entire 15-page tirade which

was based upon this point is rendered absolutely useless. Sorry, Jochen, but

"dirty tricks get ya in the sticks".

That's it??? Not at all! As explained in the

last section above, this was the pawn, and NOT the game.

Zaman claims regarding my first article that

"the entire 15-page tirade which was based upon this point is

rendered absolutely useless." That is completely wrong. The part in which

I discussed the etymology of proskuneo makes up merely 5.2% of my article (374

of 7232 words in the body of the article). I elaborated on the etymology only after I had

already established the true meaning of the word, and after I had proven that

Zaman had committed the etymological fallacy. The etymology discussion was an afterthought

in the whole argument. In other words, 94.8% of my article was not about the etymology

of proskuneo but about about its contemporary meaning, and about various general

and foundational linguistic principles related to and violated by Zaman's etymologial

fallacies. This constitutes a rather low reading comprehension by any standard.

This is also further evidence that Zaman writes "rebuttals" without making the effort

to understand the argument that he attempts to respond to. I had made that already very

clear in my article answering to his Talking

Ants in the Qur'an?, exposing several of Zaman's straw men arguments. But seemingly

he has not learned the lesson yet. Let me state it explicitly: I will not let Zaman

(or anyone else) get away with misrepresenting my arguments. If you care to respond

to my articles, then deal with the actual arguments presented in them, and don't even

think of building your case on knocking down a straw man. It will inevitably be exposed.

"Dirty tricks get ya in the sticks"?

Exactly!

[Question: Would Zaman care to clarify where he thinks I used a "dirty trick"?

Or was that just another one of his many empty accusations that he cannot back up

with any evidence?]

Apart from the obvious fact that Zaman is majoring on the minors and blowing this issue

completely out of proportion, there are several further observations to be made about

his above argument.

First, despite his confident conclusion, "That's it",

Zaman has not presented any proof. On the contrary, he only exposed that he has

no clue what actually constitutes evidence in the field of etymology. He calls himself

an etymologist, but is completely ignorant of the established methodology and accepted

working standards in this field, and I am not talking about some deep aspect in the science

of etymology that is only known to specialists. Actually, I do not know of ANY

field of studies where finding another person who shares your opinion constitutes

proof that your opinion is correct.

From a scholarly point of view, it is not good enough to base your argument on ‘scholar

X says Y’ (which would be the fallacy of appeal to authority). Rather you need to show

why Y is true, and then use scholar X to back that up. A correct approach would have been

to thoroughly show how the words are related (providing examples from Greek texts to show this,

e.g. tracking historical usages) and then one could have observed (say in a footnote) that

Strong also makes the connection. But to start one’s argument from a reference

to Strong's opinion is simply weak.

Second, we note that just as with his earlier introduction of the term

tongue-in-cheek Zaman tries again to avoid taking

personal responsibility for his errors. He does not admit to any error, but just in

case it should eventually turn out to be an error, then it is still not his

error, but the error of James Strong.

Shifting the blame for an error to the higher authority of a textbook from which he

copied it may perhaps be considered an acceptable excuse for a 7th grade highschool

student. Zaman, however, insists to be treated as a scholar of linguistics

in his own right, and among scholars the attempt to defend a wrong argument

with "but he said so" is impossible, not to say infantile. Zaman disqualifies

himself through such behavior. [Furthermore, doing so is yet another logical fallacy,

known as the fallacy of appeal to authority. As if Zaman hasn't already

committed enough logical fallacies in this article alone.]

With the above attempt to shift responsibility Zaman has effectively ranked himself

as being in a position way below Strong's in regard to linguistic authority. [Just how

much of a linguistic authority Strong's is, will be discussed below.]

Let me give another illustration. For several years I taught undergraduate

mathematics classes at university level. Even top students sometimes make

mistakes and I had to give them a lesser grade on their homework or

exam papers than they usually got. Moreover, there are the not so good students

who copy the work of good students and, in order not to be caught cheating,

introduce slight variations in the formulation of their answers. Sometimes these

variations make correct statements wrong, or slightly wrong statements become

completely wrong because they did not really understand what they were copying.

The good student gets a "B" because of some mistake, the not so good student

gets a "C" because he made that mistake even worse. He does not understand

why his grade is less and thus he comes complaining and argues that he should

get the same grade as the good student because he copied his work. Well, the

result of such complaints can only be that the grade of Mr. not so good student

drops from "C" to "F" for cheating. [If Zaman had been my student, he would

probably have argued that he should get an "A", since this was not HIS

mistake, but it was the mistake of the person he copied from! Frankly,

I have heard too many silly excuses in my life. Sorry to disappoint you,

but this approach won't work with me.]

I leave it to Zaman to decide whether he thinks that his above argument was more

appropriately compared to the behavior of the textbook copying 7th grader in

the first illustration, or better illustrated by the second one of the bad

undergraduate student. In any case, I have made my point. I will not let Zaman

off the hook: As long as he poses as the "Near Eastern and Semitic Studies

Institute of America" and makes public claims about his linguistic scholarship

I will hold him personally responsible for all his linguistic mistakes.

Finally, while doing the research for my original article on Zaman's etymological

errors, I discovered that Strong's Concordance indeed makes the connection

between kuneo and kuon. I was 95% sure that Strong's was the source

of Zaman's claim. Being convinced that Strong is wrong regarding this conjecture,

I had two options. Either, I could quote Strong's entry on proskuneo,

state why I thought that it was the source of Zaman's claim, and then proceed

to explain why Strong is wrong in order to give Zaman no way of coming back on

this issue (i.e., "slamming the door shut before it even opens", in Zamanian

phraseology). This would, however, have robbed Zaman of the opportunity to sling

all these wonderful insults at me which we can now admire in his rebuttal, and it

would have prevented him from displaying more of his deep linguistic knowledge

— or rather the lack of it — as he has then done in manifold ways.

Four weeks before publishing my article, I discussed the ‘problem’

of Strong's entry with two people. There were two reasons why I finally decided

not to comment on Strong's in my first article. Strong's entry is merely

an opinion without proof, it does not constitute evidence. Why should I make

a long article even longer by discussing something irrelevant? Zaman had not

appealed to Strong's (yet), so there was no need to refute it. On the contrary,

Zaman could then have accused me of a straw man argument, i.e. refuting what

he never claimed. Moreover, after knowing my reasons to reject Strong's, Zaman

would probably just have denied that this was indeed the source of his claims.

If I wanted him to reveal his source, then I had to make sure not to mention

that I already knew it. [Chess is not the only discipline in which it is

advantageous to think ahead a couple of moves.] Gladly, Zaman reacted just as

expected on this one.

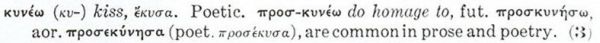

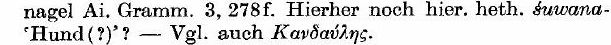

Zaman's abuse of Strong's

Let's have a closer look at what Strong's actually wrote and compare

it with the conclusions that Zaman drew from this dictionary entry.

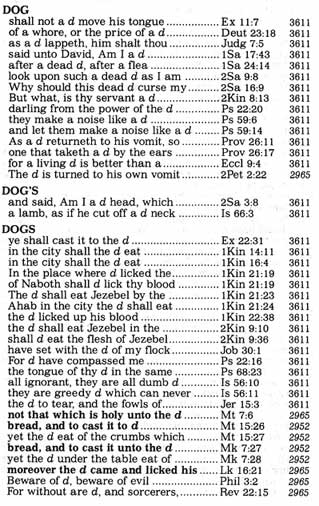

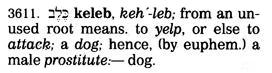

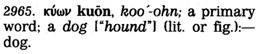

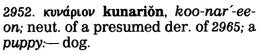

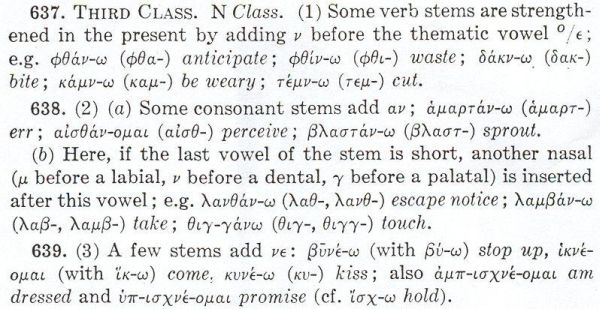

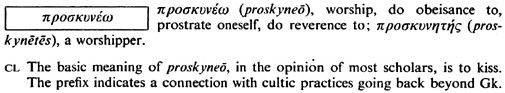

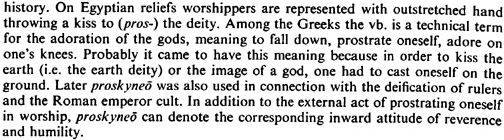

| James Strong: |  |

| Shibli Zaman: |

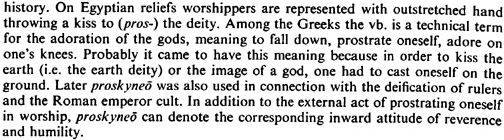

It is interesting to note that in the Greek text

the word for "worshipped" here is "proskuneo" which is a contraction of "pros" meaning

to "be in the manner of" and "kuneo" (root "kuon") which is basically a dog.

How the Biblical translators understood groveling like a dog to be "worshipping" is

dogmatically baffling to say the least.

(Orig. article) |

| |

So even if Jochen wa absolutely right that

the word pros-kunew (προσκυνεω)

has no etymological relationship to kuwn (κυων) for "dog"

(which he is most definitely not), then this is not my

"etymological fallacy" but it is James Strong's.

(His second article in defense of the first; added bold

emphasis mine) |

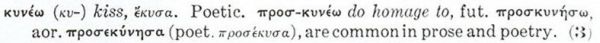

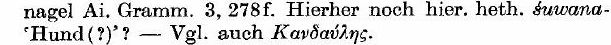

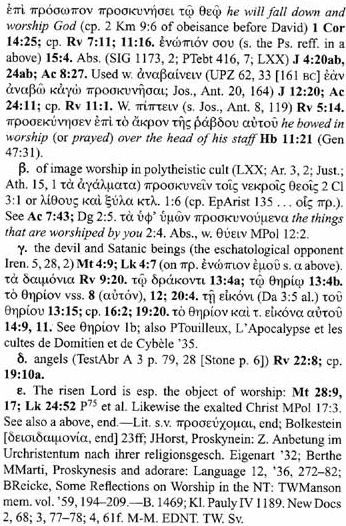

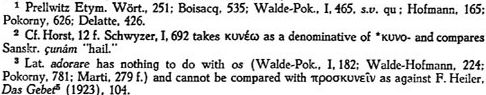

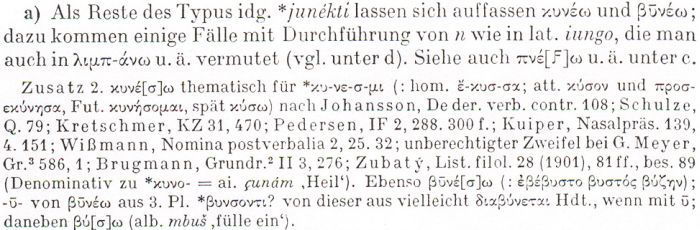

First, Strong only conjectured that the word kuneo is "a probable

derivative of kuon". Zaman, however, simply skips the probability part and argues that

this is definitely and unquestionably so. There is no expression of caution to be

found in Zaman's statements. This is the first element of dictionary abuse on Zaman's part.

What is the evidence that led Strong to the conjecture that kuneo is derived from

kuon? None is provided. Strong only stated a guess. What is Zaman's additional

evidence that allows him to argue this etymological connection not only as a conjecture

but even with certainty? Zaman did not provide any evidence at all.

Second, Zaman's methodology of selecting several unrelated elements from a dictionary

entry and then combining them into a new "meaning" (not found in the dictionary) is

simply atrocious. Let us first understand how Strong put together his dictionary

entry before we examine how Zaman misused it. Strong clearly states that kuneo

means to kiss, but since he feels (for unknown reasons) that kuneo

is derived from kuon (dog), he then tries to connect the meaning "to kiss"

with the word "dog" and comes up with "like a dog licking his master's hand".

After closing his parenthesis of etymological speculation, he does not mention

the word "dog" again. Just as Strong knows that the meaning of kuneo is

to kiss, so he knows also that the meaning of proskuneo is to "prostrate

oneself in homage (do reverence to, adore)" and it is usually and correctly

translated in the KJV as "worship". However, Strong's fondness of his conjectured root

word kuon has seemingly led him to seek a couple of words that can be used of

both dogs and humans, and so he inserted into his list of meanings also "to fawn

or crouch to" (as connecting elements between root and meaning?) before providing

the real meaning of proskuneo after "i.e. (literally or figuratively) ...".

[This is part of the reason why the little dictionary of Strong's Concordance

is not considered a scholarly resource. It was not put together in a scholarly manner

but contains much unfounded speculation.]

Nevertheless, Strong is careful not to mention dogs explicitly in his given list

of meanings. His dictionary entry does not state that proskuneo means and

should be translated as "to crouch like a dog" or anything of that sort.

He was apparently aware that there is no basis for this, not knowing of any text in

which this word is used in such a meaning. [More about this in the section about

the proper methods of how an etymology is established.]

Such caution is, however, foreign to Zaman. He has no hesitation to select one part from

Strong's parenthesis of conjectural etymology (i.e., "like a dog") and to combine it

with one of the meanings. Since in English one does not usually say that dogs "prostrate",

he searched for a word which would convey the same idea of prostrating, yet a term more

appropriately used for dogs, namely "groveling". Therefore, according to Zaman,

proskuneo now means "groveling like a dog".

[ Note: My above attempt of reconstructing Zaman's ‘thought process’

is obviously guesswork. Actually, this scenario is still giving him some benefit of the doubt.

When taking his statements at face-value then his steps for arriving at "groveling like

a dog" seem to be even worse: He is turning prepositions into verbs, verbs into nouns etc.,

see my analysis in the first article.

The meaning that Zaman claims for ‘pros’ does not even have a basis in

the Greek Dictionary of

Strong's Concordance (No. 4314) but is completely off the wall. ]

Yet, this is not all. By stating, ‘How the Biblical

translators understood groveling like a dog to be "worshipping" is dogmatically

baffling to say the least’, Zaman actually denies that "worship"

is at least one meaning and correct translation of proskuneo. With this step

Zaman went not only way beyond Strong's but lost the support of each and every dictionary

of the Greek language. This is the second element in Zaman's abuse of Strong's dictionary.

Third, Zaman's above statement confirms again that he has no idea what the

‘etymological fallacy’ is, despite posing as a scholar and researcher

of etymology. The concept of an etymological fallacy

was explained and discussed at great length in the first part, and is now assumed

as understood.

James Strong simply stated his conjecture that kuneo (κυνεω)

is probably a derivative of kuon (κυων). This may be a wrong

etymology (and thus an error of fact) but it is not the etymological fallacy.

The etymological fallacy is assuming that the root meaning of a word is to be used

in exegesis — despite the fact that the so called ‘root meaning’ was

not in the mind of the user (writer or speaker) of the word. James Strong

did not say that we should bring dogs into understanding the NT use of

proskuneo. Even though James Strong's dictionary entry is hardly an example

of careful and responsible scholarship, he was still able to distinguish between

the real or conjectured etymology of a word and its actual meaning.

It was Shibli Zaman alone, who explicitly imported the alleged etymon kuon (dog)

into the current meaning of the word and claimed that proskuneo means

"groveling like a dog" (and that this alone is its real meaning). Therefore

Zaman alone is guilty of the etymological fallacy (not Strong) and, worse,

he does not even know what said fallacy actually is. This bears repeating since

it is so essential: Zaman alone has committed the etymological fallacy while

Strong has simply made an error in his supposed etymology. These are two entirely

different errors since even if Strong was right, Zaman would still be in error.

The above statement about Strong is actually unfair because it does not take into

account the historical context. Let me therefore reformulate: By modern standards,

Strong's dictionary seems not to be an example of careful and responsible scholarship.

However, James Strong did not have the benefit of all we now know about linguistics.

Zaman, on the other hand, does have the benefit of the discipline of modern linguistics

and, furthermore, claims to be a skilled practitioner. There is no excuse for him on

these grounds.

Is Strong's a scholarly resource?

On the very same day that Zaman appealed to Strong's Concordance as proof

for his claim regarding the etymology of proskuneo he also published a second

rebuttal article in which he dismissed Sam Shamoun's quoted sources with this reasoning:

II. Scholarly vs. proletarian evidence

Mr. Shamoun proceeds:

"According to Greek Grammarian William D. Mounce: 'There is ...'

(Basics of Biblical Greek Grammar [Zondervan Publishing House:

Grand Rapids, MI 1993], p. 302; ...)"

It is unfortunate for Mr. Shamoun who appealed to it,

Basics of Biblical Greek Grammar is a very novice textbook.

With all due respect to its author, it is not an exhaustive reference

for Greek grammar by any stretch.

(Shibli Zaman,

Forgive Them,

For They Know Not Greek, 28 July 2003; bold emphasis mine)

Although Shibli Zaman has apparently great problems in distinguishing what is a scholarly

resource, and what not, and in selecting the

appropriate scholarly reference for those linguistic questions he chooses to

discuss, the question whether a certain reference is scholarly and trustworthy is certainly

important. This section is, therefore, devoted to determine whether Strong's

is generally considered a scholarly resource or not.

First, one needs to take seriously the full title of Strong's, i.e.

Strong's Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Even though this book also has

an appendix with a small Hebrew-English and Greek-English dictionary, Strong's

is first of all a concordance of one particular English translation of the Bible,

the King James Version. It was never designed to be a serious Greek or Hebrew

dictionary. It is not a lexicon and it is no real guide to etymology or morphology.

At the time of its publication in 1890 this concordance was a momentous achievement

and it is still very useful as a concordance. But if one needs to consult

a dictionary one should look elsewhere.

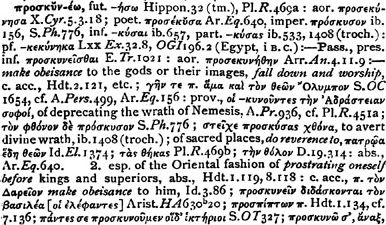

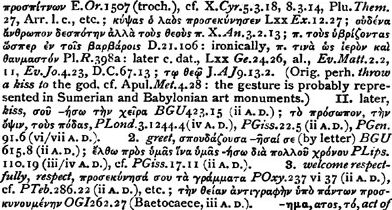

For background information on the problem of "etymology in old dictionaries"

let me begin with this quotation:

ETYMOLOGY

is word history. The etymology of a word is its history from its

beginnings, including its forms and its meanings as far back as these

can be documented and its record of being borrowed and adapted into

other languages. As etymologists bring the record forward or

trace it backward, they try where they can to explain whatever linguistic

and semantic change they encounter. Although science is a necessary part

of it, etymology is finally as much art as science, and many of

today’s dictionaries have been obliged to substitute the more accurate

comment “origin unknown” for what were once thought to be good

guesses at the etymology of many words. Likely possibilities

are simply not the same as proofs. (Kenneth G. Wilson, The Columbia

Guide to Standard American English, Columbia University Press, 1993;

online

source; bold emphasis mine)

We have already seen that Strong injected much speculation and guesswork in his

entry on proskuneo. This is a serious problem throughout his little dictionary

and has led to many abuses ever since its publication. There is not only the problem

of people who abuse it for polemical reasons like Zaman, but also many honest and

devoted Bible students without linguistic training have been led astray by taking

up Strong's etymological speculations and pushing them into their exegesis, thus

committing the etymological fallacy over and over again.

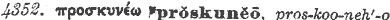

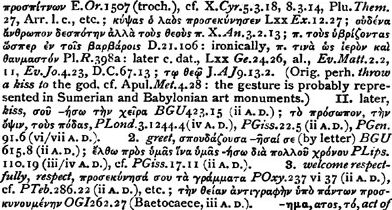

In 2001 Zondervan Publishing House issued an updated and revised Strong's Concordance

under the title The

Strongest Strong's Exhaustive Concordance to the Bible. The promotional for this

edition makes the following statement:

Strong's dictionary methodologies are flawed by what has come to be called "root fallacy."

He assumed that biblical words could be defined by the sum of their parts. But we know

that a pineapple is not an apple that grows on pine trees, nor is a butterfly a fly that

lives in butter. Our dictionaries are based on the latest lexicons and word studies,

reflecting the significant advances in biblical scholarship of the past half century.

And The Strongest Strong's is the only edition to contain up-to-date Greek and

Hebrew dictionaries. (bold and underline emphasis mine,

this paragraph as scanned image,

original

source [1 MB file size!])

A similar statement is also found under the heading "Improvements in the Strongest Strong's",

in the Introduction of this edition. Since Zaman has such a bad track record regarding

understanding things the first time around, ... let me quote this slightly different

formulation as well:

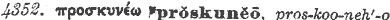

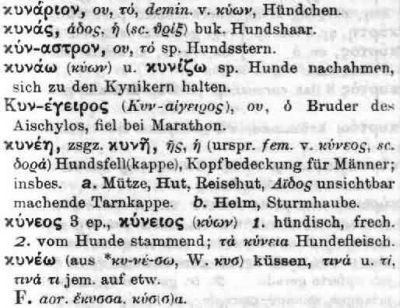

Fourth, Strong's dictionaries are flawed by a methodology of the nineteenth

century that has come to be called the "root fallacy." He assumed that biblical

words could be defined by the sum of their parts. But just as we do not think

that a pineapple is an apple that grows on a pine tree or that a butterfly

is a fly that likes butter, so we should not use this methodology to define biblical

words as was so common in the nineteenth and even the twentieth centuries.

Our dictionaries are based on the latest dictionaries, lexicons, and word study

books, reflecting great advances in biblical scholarship.

(Source: The Strongest Strong's Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible,

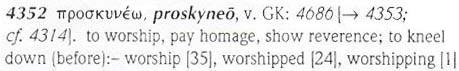

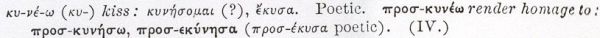

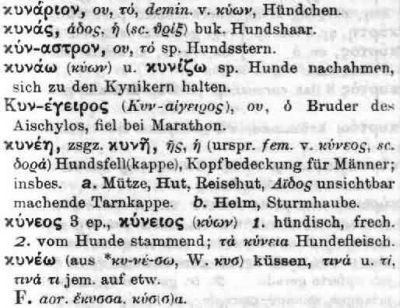

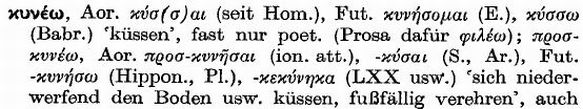

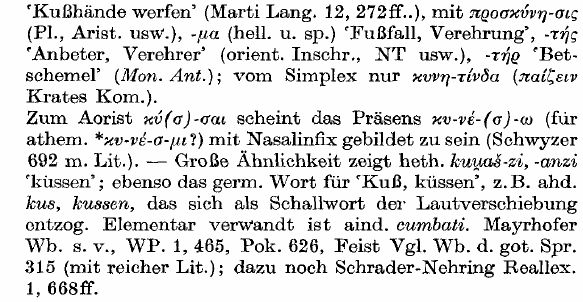

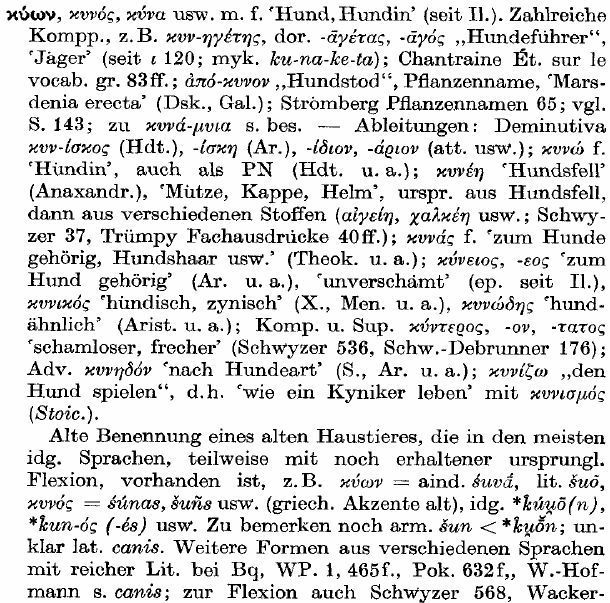

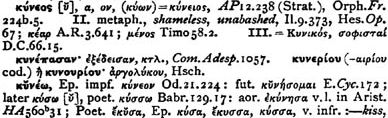

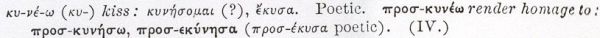

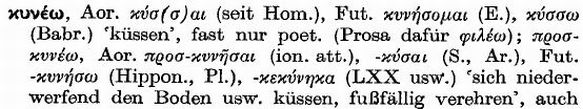

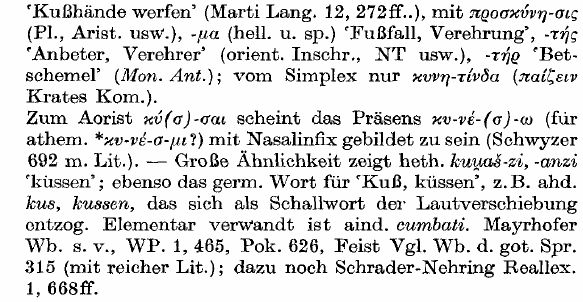

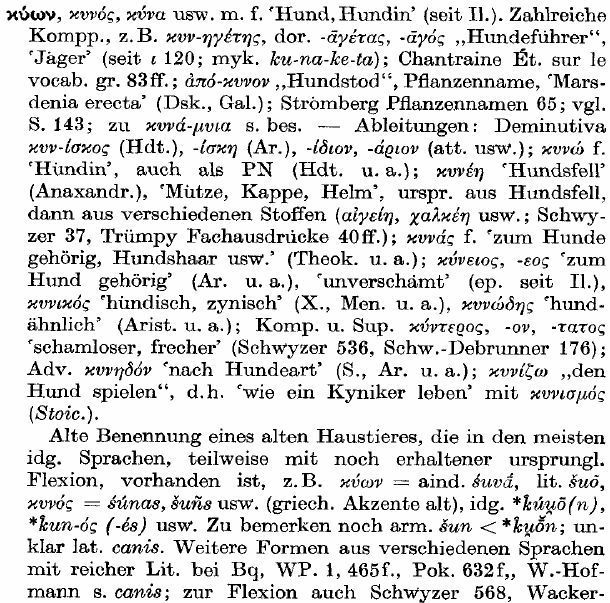

21st Century Edition, by James Strong, LL.D., S.T.D., fully revised & corrected